I.D. Antarctica 2023 – Week #1 Mystery Creatures

Hello and welcome to Investigate and Discover (I.D.) Antarctica 2023!

We are excited to share our Antarctic experiences and research this year with you all. After some exhausting travel by air and by sea, we arrived in Antarctica on 29 December 2023, but we want to catch you all up on our journey before jumping into our current research on the many organisms that live in the Southern Ocean.

We all flew from our various homes in the United States and met in a port at the bottom of South America called Punta Arenas, Chile. This beautiful and interesting city is loaded with culture and history. It was one of the most popular ports for Antarctic exploration going all the way back to the 1920’s.

“Hurry up and wait” was the most accurate description of our port call. Maya was one of the first scientists to make it to Punta Arenas and, after a much-needed shower and a few hours of sleep, she was already thrown into the fast-paced ship life mentality. There was much cargo to be loaded onto our research vessel, the R/V Laurence M. Gould (pictured below), but we had to wait for everyone to test negative for COVID before boarding the vessel and beginning our preparation.

The next few days passed by in a very happy blur. Our lab, which is made up of Maya, Andrew, Tor M.L., Meredith N., and Joe C., were able explore Punta Arenas outdoors – including touching Ernest Shackleton’s (the most famous Antarctic explorer) foot for good luck and calm seas during our journey.

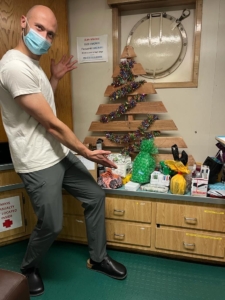

We spent an entire day transporting boxes, organizing and labeling every drawer, and setting up our equipment. We finished with just enough time to decorate with some holiday cheer before we departed on 23 December 2022.

To get from Punta Arenas to Antarctica, we must cross the roughest section of ocean in the world – the Drake Passage. The waves in the Drake Passage can frequently top 30ft and winds often approach 60 mph. It takes us about 5 days to cross the Drake, which unfortunately included Christmas this year. All the scientists and support staff on the Gould (~30 people) brought small gifts for a White Elephant present exchange which was a lot of fun. We even made a Christmas tree out of an old wooden pallet! Not everyone on the ship celebrates Christmas, but we all missed home and stable(!) land at this point and joined together to embrace our new community.

The Drake Passage is also home to an incredibly interesting group of animals with extreme lifestyles. There are many unique sea birds that spend most of their time hunting food in the Drake.

This year, we were fortunate to see and photograph several species. For example, below is a picture of a Royal Albatross (Diomedea epomophora). In addition to its common name (Royal Albatross) we included its scientific name in parentheses – Diomedea epomophora. This is common notation when referring to species in scientific literature.

The first part of scientific names, Diomedea in this case, always represents the genus of an organism and the second part, epomophora, always represents the species name. Scientific names look and sound like a different language because they often are often in Greek or Latin!

While an animal can have several common names in different countries and oceans, all animals only have one scientific name. While these names can be hard to pronounce and remember, they are an important tool for correctly identifying organisms across different regions and languages.

Albatrosses can be especially tricky to identify to species-level, so we had to ask for some help from our friends on the ship that study birds (@palmer_birders) to figure out it was a Royal Albatross. This remarkable species has one of the largest wingspans of any living bird on the planet – 11ft! They are also incredibly fast flyers (reaching speeds of 70 mph) and travel an estimated 118,000 miles each year! They often go several YEARS without ever stepping foot on land and can live to ~60 years old. What a truly remarkable bird.

Although we know sea birds in the Drake Passage are hunting for food, its rare for us to actually see them capture and eat their prey.

This year, Andrew was able to photograph a sea bird with a zooplankton in its mouth! We both study zooplankton, which are broadly defined as organisms that drift or weakly swim through the upper part of the ocean. Although zooplankton are often quite small in size, they can also be as big as jellyfish! We’ll show more examples of zooplankton next week.

Mystery #1

Can you use the Sea Bird and Zooplankton Dichotomous Keys to identify the species of bird and what zooplankton its eating?

Here is another picture of the same species of bird in flight:

Mystery #2

We were thrilled to witness this cool example of predation. As we neared closer to the coast of Antarctica, we couldn’t believe that we saw another species of sea bird hunting and eating the same species zooplankton! Clearly this zooplankton is an important part of the Antarctic food web.

Can you also identify the species of bird in these photographs below? It’s a little harder to see the zooplankton in its beak, so the other sea bird might be easier to use first.

Here is another picture of the same species.

Can you identify these two mystery seabirds using the Dichotomous Keys linked above?

Come back to this blog in a few days to check your answers!